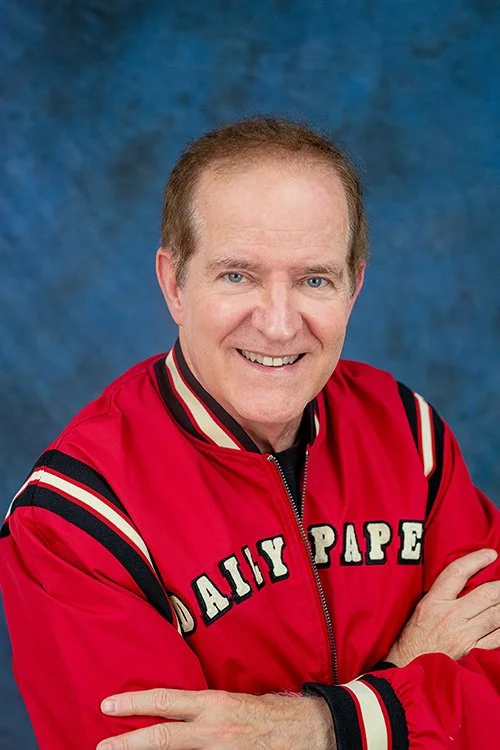

Morley Swingle

Morley Swingle is a former prosecutor now writing mystery/thrillers, each one featuring at least one murder and at least one courtroom scene. They say to write what you know. Although he hasn’t murdered anyone (yet) Morley prosecuted 111 homicide cases during his career and tried 178 jury trials. He usually won, but the occasional loss kept him refreshingly humble.

An avid writer even when working long hours as an attorney, Morley published his first novel, The Gold of Cape Girardeau in 2002. It won the 2005 Governor’s Book Award in excellence from the Missouri Humanities Council, and was praised by Elmore Leonard as “the most amazing historical novel I’ve ever read.” His second novel, Bootheel Man, was a finalist for the 2007 William Rockhill Nelson Award for excellence in fiction. Being complimented by Elmore Leonard, one of Morley’s heroes, made Morley’s head swell.

In 2007 Morley published a true crime memoir of his first twenty years as a prosecutor, collecting real-life stories of his most entertaining and fascinating cases. Scoundrels to the Hoosegow: Perry Mason Moments and Entertaining Cases from the Files of a Prosecuting Attorney was lauded by Vincent Bugliosi as “consistently fascinating” and “highly recommended.” This compliment from yet another hero started making it more difficult to remain humble.

In 2009, Morley’s short story “Hard Blows” was selected from over 270 entrants to be featured in the Mystery Writers of America anthology The Prosecution Rests. Publisher’s Weekly singled out Morley’s story as “dramatizing the challenges prosecutors encounter” and called the entire book “consistently high quality.” Morley’s story was a finalist for the 2010 Barry Award as the Best Mystery Short Story published that year. It also earned an Honorable Mention in Otto Penzler’s The Best American Mystery Stories.

Morley has published numerous law journal articles and law manuals. In 1995, his article on prosecutorial ethics entitled “Warning: Pretrial Publicity May Be Hazardous to Your Bar License,” won the W. Oliver Rasche Award from the Missouri Bar Association for being the “most outstanding article” published in the bar journal in 1994. He had never heard of the award until he won it, but after learning it existed he tried for it over and over, finally winning it a second time in 2013 for his article on warrantless searches of smartphones.

In 1992, the FBI selected Morley as one of only 50 prosecutors in the nation (one from each state) to attend and graduate from the Advanced Course for Prosecutors at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. Morley found the audience (other prosecutors) even more interesting than the instructors, since he sat between the prosecutor of Jeffrey Dahmer (for serial murder) and the prosecutor of Mike Tyson (for rape).

In both 2003 and 1992, the Missouri Mothers Against Drunk Driving named Morley as Missouri’s “Prosecutor of the Year.”

Two of Morley’s cases made it to the United States Supreme Court. The prosecution won one and lost one, which is an excellent batting average in baseball, but not so good in appellate advocacy work. All together, he personally briefed and/or gave the oral argument in nearly 40 appellate cases in both state and federal court, and won most of them.

Morley taught the “Criminal Law Update” at the Missouri Judicial College every year from 1993 to 2010, teaching Missouri’s trial judges the latest developments in criminal law. It was a tough audience, since somewhere in the crowd would lurk the judge who presided over every case Morley would be discussing, and those darn judges would delight in catching Morley in even the smallest mistake.

Morley served 18 years on the Missouri Supreme Court’s Criminal Procedures Committee, which writes the book containing pattern jury instructions used in every criminal case in Missouri. You won’t want to read that book unless you are either litigating a criminal case or having trouble falling asleep.

Click to enlarge.

In Morley’s first case out of law school, he represented a client who sought the unheard of thing (at the time) of a non-smoking area at work. The case Smith v. Western Electric Company, 643 S.W.2d 10, 37 A.L.R. 4th 473 (Mo. App. E.D. 1982) established the duty of an employer to provide a non-smoking area for employees, and laid the groundwork for a parade of tobacco litigation to come nationwide. The American Lung Association featured Morley as its keynote speaker at the tender age of 27 at its national conference in 1982. Morley would have made tons of money in tobacco litigation had he stayed in private practice rather than switching to the prosecutor’s office. His judgment regarding money matters has always been questionable.

In 2007, the University of Missouri-Columbia awarded Morley membership in the Order of the Coif, which is a big deal to lawyers, but probably doesn’t provide the same inner glow as winning an Edgar Award (not that Morley would know how that glow feels just yet). The closest he’s gotten to an Edgar Award is attending the banquet in New York City.

From November 2013 to March 2016 Morley worked as a criminal defense attorney in Denver. During that time he handled more than 100 cases from the defense side, and defended clients in seven jury trials, winning almost all. He discovered, to his shock, that prosecutors can sometimes be unreasonable and foolish. He followed legendary defense lawyer Melvin Belli’s practice of raising the Jolly Roger pirate flag outside the office after each courtroom victory.

Books and chocolate are two of Morley’s three favorite things.

Morley owns a German shepherd who excels at catching Frisbees. He also owns two cats, neither of whom would bother catching one if life depended upon it.

Morley always has a pile of books on his bedside table. Favorite authors include Mark Twain, Scott Turow, Elmore Leonard, Robert Crais, J. K. Rowling and Stephen King. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and Blood Work by Michael Connelly are two of his all-time favorites.

Morley has been a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team for years. During the COVID season, he bought a season ticket as a cardboard replica (yes, he paid for the privilege) and a Harrison Bader homer hit the cardboard Morley sitting in the left field bleachers.